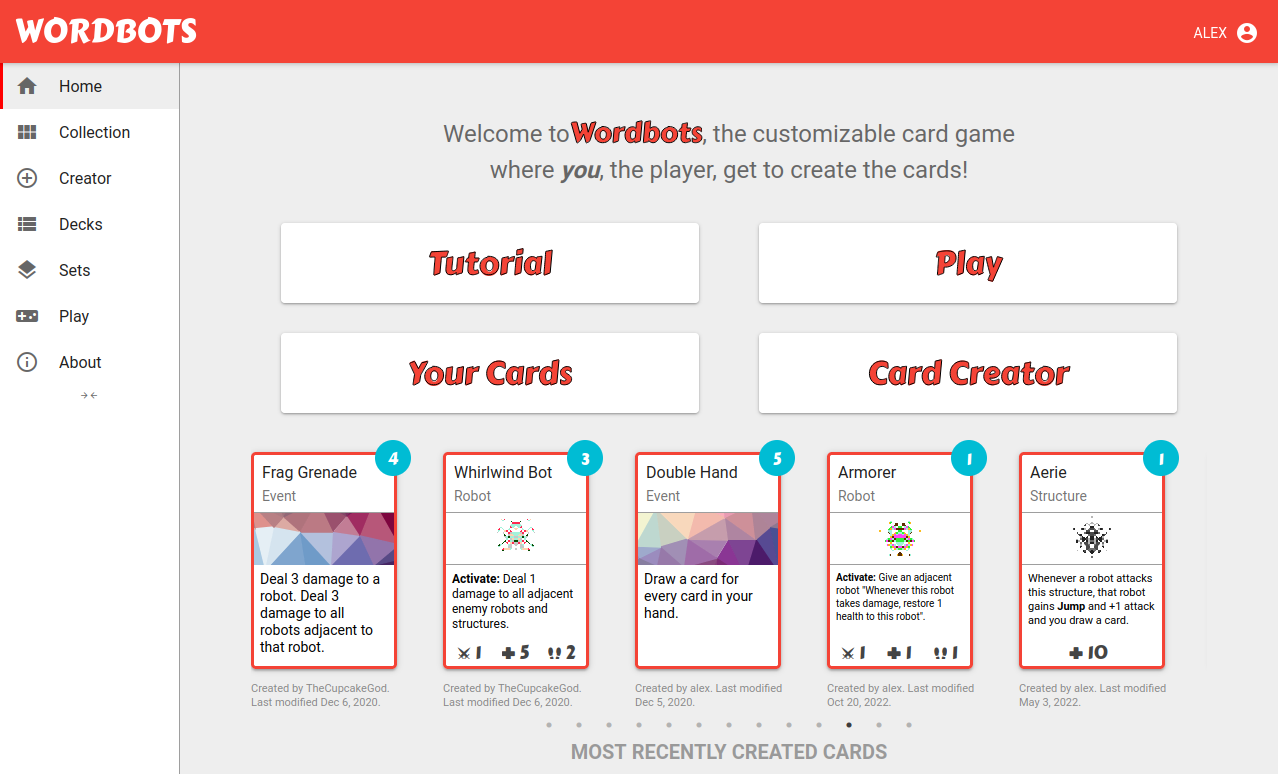

About a year ago, I “released”* Wordbots, the tactical card game with user-created cards that I’d been working on since 2016.

(* I say “released” in quotes because this isn’t really the sort of game that will ever become feature-complete, especially not as a side project. But on April 29, 2023, I declared it fully playable and ready to graduate from alpha into a permanent “beta” stage, in which I’m no longer actively developing new features but continue to fix bugs and make minor improvements as time permits.)

Getting Wordbots from concept to fully playable beta was a journey. It was one of the hardest things I’ve done in my life and by far the largest project I’ve ever started, in all senses of the word – the biggest in scope, the most time-intensive, and the most emotionally draining to work on. Would I have started working on Wordbots if I’d known how long it would take and what a torturous path I’d go on to “finish” it? I’m not sure. But in any case, I’m glad I did it.

I set out to write a brief retrospective covering my experience developing Wordbots, from start to finish. I didn’t expect to write 6,000 words on the topic, so my apologies for the length of this post – I guess I had a lot to say!

(For those new to Wordbots, here’s some information about what is, and here’s more about its technical underpinnings!)

Table of contents

- First, a visualization!

- A (not so) brief history of Wordbots

- What went right

- What went wrong

- Final thoughts

- Acknowledgements

First, a visualization!

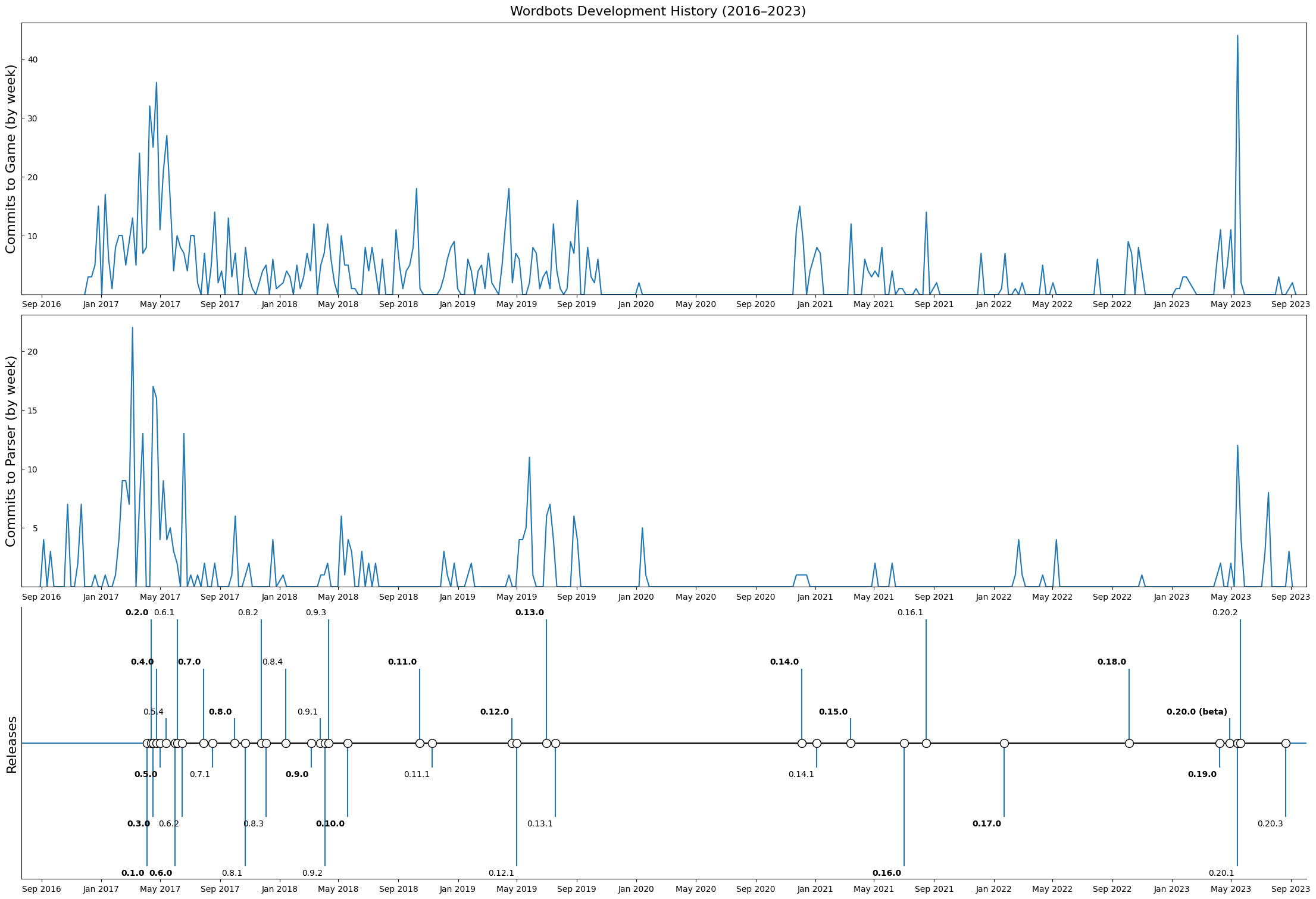

Before I talk about my successes and challenges with Wordbots, it might be helpful to throw up a little graph I made illustrating the development process as the story of git commits and releases, from my first-ever parser commit to just after the beta release:

I should mention that I was fortunate to have a lot of help throughout this process, especially from my brother but also from a whole host of people who made contributions of code or art or playtesting or feedback, who are credited here. Still, for various reasons, I ended up making the vast majority of commits for both the core game and the parser, so this chart represents both the development cadence of Wordbots as a whole and my own personal journey working on it.

As the chart makes painfully clear, working on Wordbots was not a totally smooth process. Let’s dig into how it all went down.

A (not so) brief history of Wordbots

The beginning (summer 2016–fall 2017)

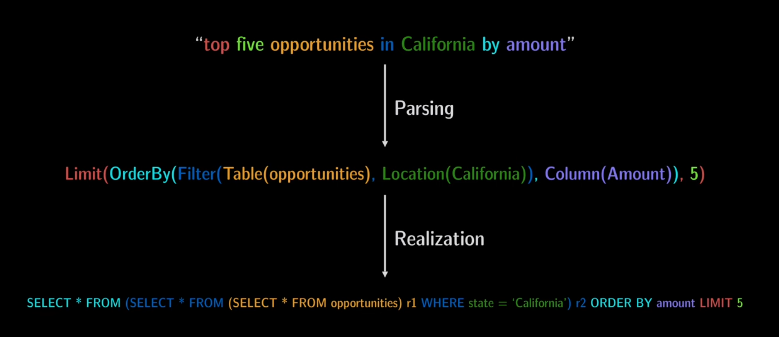

The original idea for Wordbots came to me as I was working on open-sourcing Montague, the semantic parsing library that I’d worked on with Joseph Turian and Thomas Kim at the long-forgotten NLP startup UPSHOT.

At its core, Montague is a fancy CKY parser that parses a CCG grammar and maps parsed tokens to semantic definitions, given as lambda-calculus terms in a provided lexicon. It is ancient technology by NLP standards (after all, the CKY parsing algorithm dates back to a 1961 paper), but we came up with a clever design that ties these concepts together in a user-friendly way. In essence, Montague took something that had been possible for decades (domain-constrained semantic parsing) and made it more accessible and (dare I say?) fun to implement.

Our original use case for semantic parsing at UPSHOT was translating English to database queries – hardly riveting stuff. But as we were writing the documentation for Montague, I began to brainstorm other possible applications for it, initially to figure out how to communicate the breadth of what our parser was capable of.

After working through a few toy examples, I started thinking of what semantic parsing could be used for within a gaming context. I thought back to card games like Magic: the Gathering and Fluxx, where individual cards (in Fluxx, sometimes even player-made cards!) could completely alter the game’s rules. I’d also recently played and enjoyed the now-defunct online tactical card game Atomic Brawl and imagined a similar style of card game with cards that players could make themselves, with the card text automatically parsed and translated to a programming language, perhaps JavaScript. While writing the Montague README, I even mentioned this idea as an “exercise for the reader”:

Applications Exercise 5. † Game semantics. Come up with a semantic scheme for representing rule descriptions for a simple card game (think Magic, Hearthstone, etc., but simplify!) For example, a card may say something like “Whenever your opponent loses life, draw a card”. Then write a parser for it.

We open-sourced Montague in March 2016, and Joseph and I gave a talk about it at the Strata conference that June. That fall, I started playing with my game idea, building up a lexicon in Montague that could handle simple actions and trigger expressions like "At the end of each turn, each creature takes 1 damage"` and turn them into JavaScript code. But there was still no actual game that these cards supported – it was just a tech demo with an artificial lexicon vaguely evoking a positional card game.

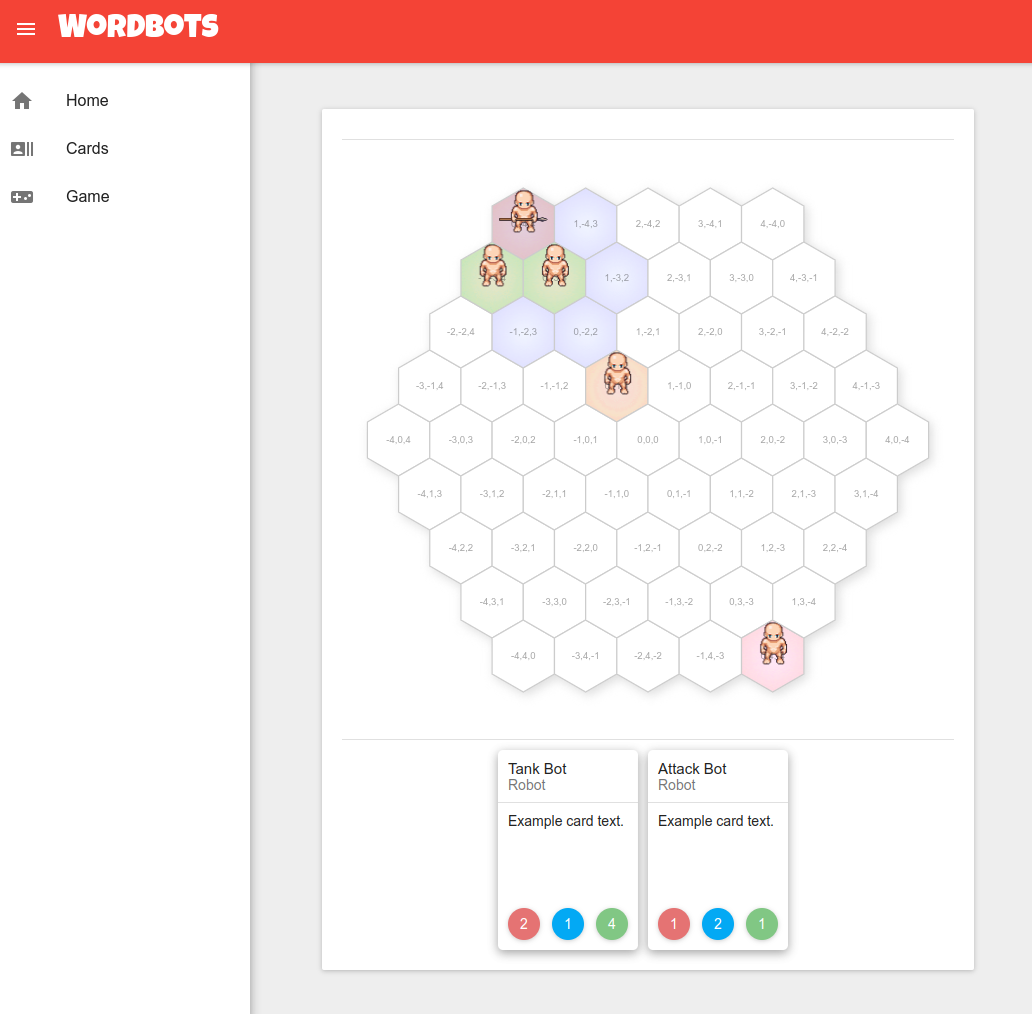

While visiting my family over Thanksgiving, I showed my brother Jacob what I’d built, and he was clearly as excited about the concept as I was. He had some React experience at the time (I didn’t yet), and we quickly threw together a game prototype in React over the long weekend, using Hannu Kärkkäinen’s react-hex-grid library for the hex grid rendering and logic. By the end of the year, we had a barebones UI that could render a board and cards – nothing resembling a game yet, but enough of a skeleton that we could envision a path forward:

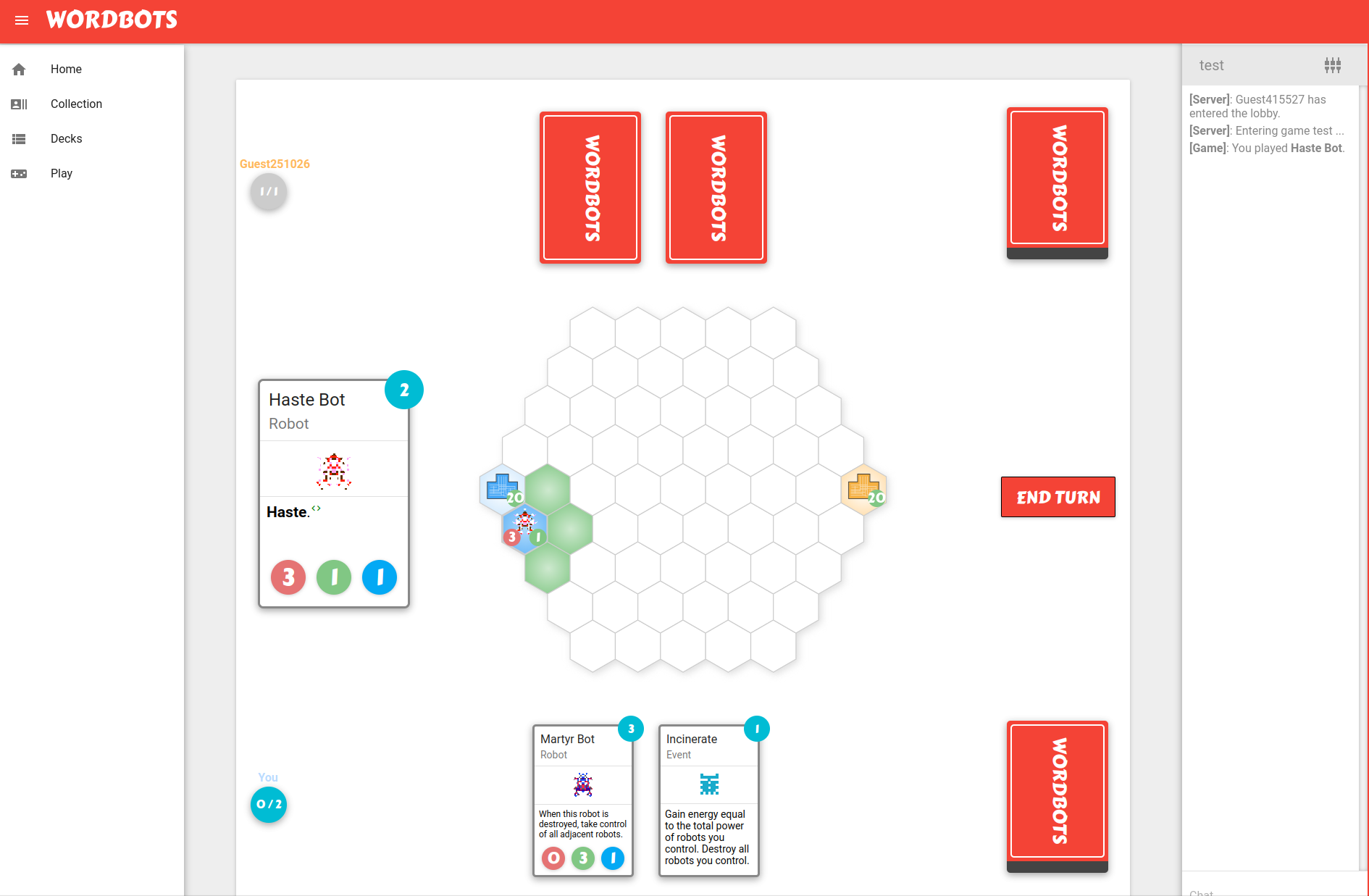

I left my job at the start of 2017 and decided that I may as well take advantage of my newfound free time. I resolved to stay “funemployed” until the end of the year and try to finish Wordbots by then. I started working on Wordbots full-time in January, gaining proficiency in the React ecosystem along the way, and Jacob and I were able to make rapid progress on the prototype. By early April, we reached our v0.1.0 milestone: a fully functional prototype with working card creation and multiplayer gameplay, albeit limited features aside from that (and it certainly wasn’t much to look at!):

Progress continued quickly as I built up steam. By the end of April (v0.4.0), we had spectator support, activated abilities, card import/export, turn timer, and a huge amount of new card mechanics. By the end of May (v0.5.4): user accounts, auto-generated documentation, SFX, and more card mechanics. June (v0.6.2): tutorial mode and the “Did You Mean” feature in the card creator. July (v0.7.0): practice mode, in-game animations, and a major UX redesign.

We were quickly running through our initial feature roadmap, and an end seemed in sight. But I couldn’t maintain this pace for long.

Slow but steady improvement (fall 2017–summer 2019)

I’d planned to take all of 2017 off of work, but for various reasons (including a health insurance snafu), I ended up interviewing again in the summer. I started my current job in the fall, and this, combined with a couple of big international trips that I took in quick succession, got me out of the Wordbots groove.

The next few months didn’t bring many major new gameplay features. With my more limited free time, I worked more on ironing out things at the margins: tweaking the UX, fixing bugs, adding new things to the parser, and generally trying to make things more user-friendly.

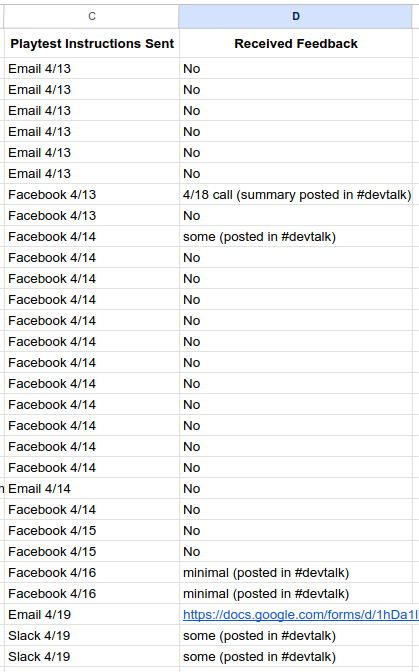

In April 2018, Jacob and I felt the game was sufficiently polished for an official playtesting round. We’d shown it to a few people before, but never anything like this: we solicited participants in our social networks, ultimately sending out a link as well as some playtesting guidelines to 30 of our friends. And then we waited … And waited … And waited … Of our 30 playtesters, only two gave us substantial feedback, and the vast majority never responded at all. As far as I could tell, even people who really wanted to try Wordbots seemed to have been thoroughly stumped by the experience of trying to “play” it.

Needless to say, the failed playtest round was demoralizing for us. Still, it was helpful, if disheartening, to learn that our new-player user experience was, to be frank, garbage, and we began to rethink our priorities. One critical conversation that started from this was our attempt to answer a question that we’d been punting on up until this point:

After all, if players can design any cards they want, nothing is stopping a player from making some kind of “Win the game immediately” card and stuffing their deck with it. And this would be totally legal in the only Wordbots gameplay format that existed at the time (we now call this the “Anything Goes” format and discourage people from playing it except with their friends).

We brainstormed a few possible solutions to the fairness question:

- Use some kind of ML model to predict how powerful given cards are and assign them in-game energy costs accordingly?

- Set up a server constantly simulating games between AI players with various cards to determine empirically how effective each card is in practice?

- Set up some kind of market-based mechanic where players could trade cards for in-game currency, where a given card’s market value would determine if it was a “fair” card or not?

- Allow players to make whatever cards they want, but establish game formats where each player is equally likely to have access to an overpowered card in-game?

The final approach seemed to be the only feasible one. Based on player feedback (thanks, Adam B!), we developed a format we called Shared-Deck (later renamed Mash-Up), where each player brings their own deck to the game, but both players’ decks are shuffled into one mega-deck that both players draw from throughout the game. The Shared-Deck/Mash-Up format injected new life into Wordbots and made matches exciting again. For perhaps the first time, I actually found myself having fun playing Wordbots with people, not just developing it.

In the fall, thanks to some word-of-mouth among Jacob’s friends, we’d assembled a small team of people interested in working on Wordbots and even started holding regular standups. Unfortunately, it proved hard to divide the work, and Jacob and I still ended up doing the bulk of it. Still, having the regular cadence of standups helped maintain developer interest, at least amongst Jacob and me. And our broader team provided a useful sounding board for trying new ideas and for deciding how to prioritize our work.

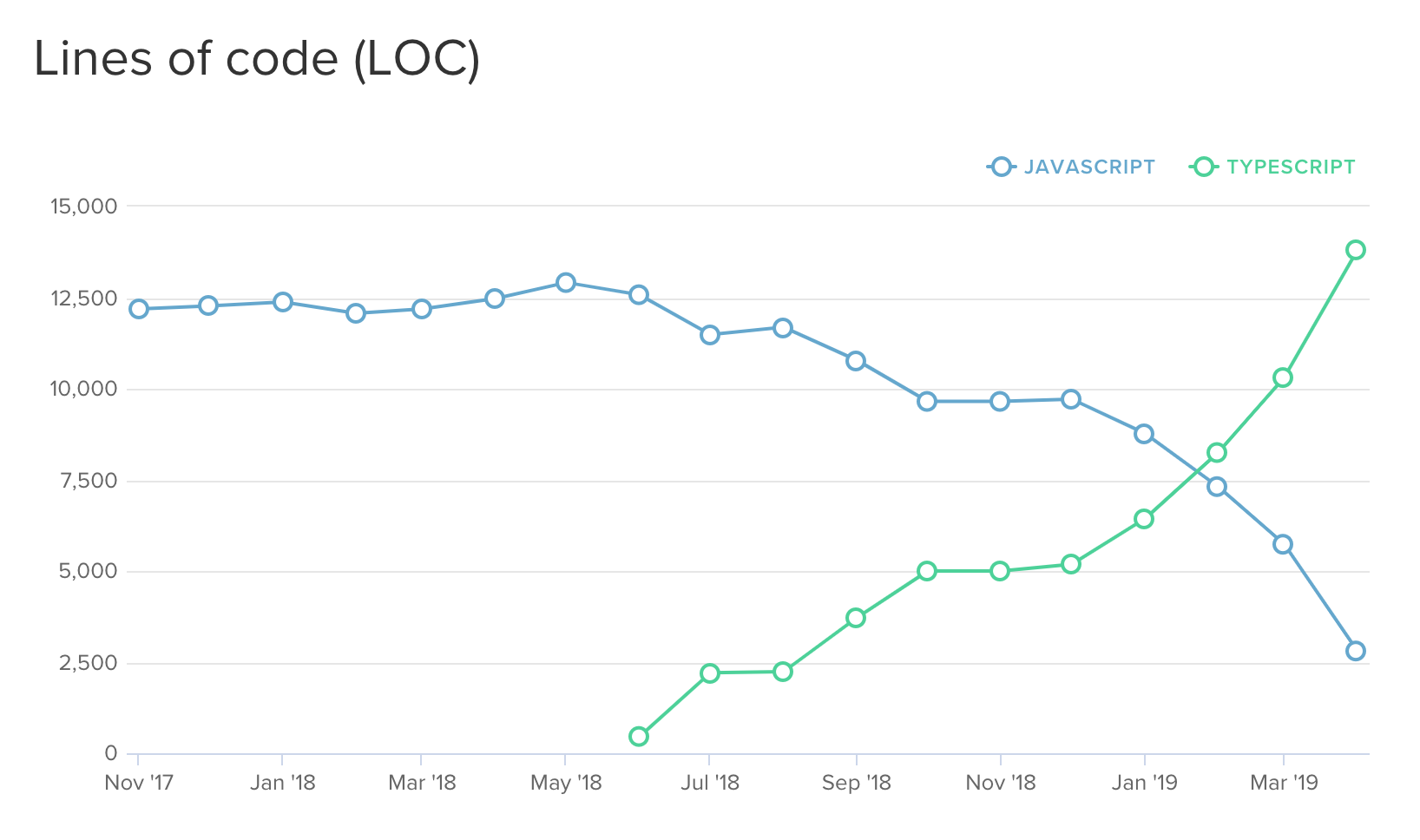

Around this time, a succession of particularly hard-to-catch bugs convinced us that it would be worth it to begin migrating the codebase from JavaScript to TypeScript. I was initially leery of such a massive undertaking but was convinced to try TypeScriptifying a little bit at a time, starting with the particularly brittle multiplayer code (and eventually ending, about two years later, with the React components). Little by little, we gained type safety throughout the Wordbots client code. Though it was a slog at times, the TypeScript refactor ultimately paid dividends by eliminating whole classes of bugs and making significant chunks of our code easier to reason about.

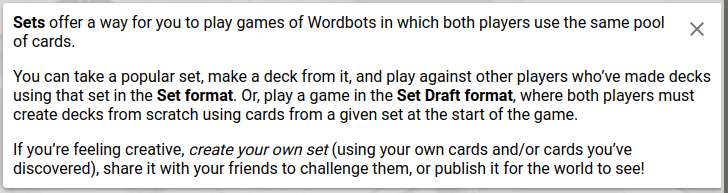

In April 2019, with v0.12.0 of Wordbots, we introduced the concept of “sets”, another answer to the “making Wordbots fair” question. Sets provided a way for players to curate their own collections of cards and challenge other players to make decks using only those cards. Finally, there was now a way for players to build and use thematic decks of player-made cards without worrying about huge power imbalances.

I intended Sets to be the last major concept added to Wordbots and began to think about what it would take to finally release the game to the wider world. I wrote a document called “Wordbots: The Final Stretch,” spelling out the remaining tasks needed to finish Wordbots, in the four categories of User-Friendliness, Robustness, Community, and Accessibility. Of course, “final stretch” turned out to be a little optimistic.

Distractions and demoralization (summer 2019–summer 2022)

By the summer of 2019, the amount of free time I had to spend on Wordbots plummeted once more as I began to spend every available weekend going to open houses, as part of our quixotic quest to buy a fourplex with our friends to live in – another massive “side project” with huge emotional highs and lows, that perhaps I’ll write about at a later point. In December 2019, we finally closed on a fourplex that ticked off all our boxes but required renovation on a massive scale. And, of course, we know what happened at the start of 2020. We were very fortunate to have the built-in community of our fourplex housemates to weather the lockdown with, but it was still an emotionally draining time. I had the mental bandwidth to manage precisely one project in 2020, and that ended up being the home renovation work, which took the better part of the year and was all-consuming while it was happening.

When I circled my thoughts back to Wordbots in this period, I could no longer picture the end goal; it was just a mountain of work that looked more and more daunting as I spent more time away from it. I began to dread the thought of working on Wordbots, but at the same time, I felt guilty for not working on it. There were times when I couldn’t sleep because I was so angry with myself at “wasting my time”, for putting so much work into this project just to abandon it …

Throughout it all, I did manage some intermittent bursts of motivation to work on Wordbots. I was able to finally finish that massive TypeScript refactor by the end of 2020 – it was a good thing to work on while my motivation was limited because I could think of it almost as a puzzle of getting all the types to line up. Around this time, I also slogged through a significant refactor of how cards are stored in the backend, developing a much more robust system of metadata tracking for cards that fixed a number of bugs and enabled many small quality-of-life features down the line.

During a weeklong “Wordbots retreat” in the Lost Coast (a location strategically chosen for poor network connectivity and few distractions) in the summer of 2021, I powered through the work of creating the Set Draft format, a feature that we’d been discussing as a team for a while, and that quickly became my favorite way to play Wordbots. Drafting provided an elegant solution to the “fairness” issue (since either player was equally likely to draft a given card) while also removing the friction of players having to create a deck before playing. With the Set Draft format implemented in v0.16.0, I could finally see the path forward that had eluded me for the past few years.

Other than that, the major gameplay improvements during this time were all aimed at providing a better UX for new players, including a massive interface redesign, art by Chris Wooten, Help and Community pages, a “New Here?” feature, and more flavor throughout the game, as well as flavor text support for cards.

The final push (fall 2022–spring 2023)

I was finally able to get out of my slump and really mount a concerted effort to finish Wordbots in fall of 2022. I’d planned a two-month sabbatical from work to work on another project that fell through at the last minute, so I unexpectedly had a whole bunch of free time, so much free time that after a while I was finally able to push through my mental block and start working on Wordbots in earnest.

In October 2022, I added one final major parser feature – and one that I could only have implemented while on sabbatical because of its colossal complexity – card rewrite effects. Finally, Wordbots had an actual gameplay mechanic that no other card game could match – cards could rewrite the very text of other cards. It’s certainly a silly addition to Wordbots and perhaps not worth the ROI on the effort spent to make it possible. But it makes me smile, and so into the game it went.

I also put a lot of work into a detailed “How It Works” page describing the technical background behind Wordbots. I figured that, even if Wordbots was never going to be a successful multiplayer game with a thriving community (and at this point, I was resigned to this fate), at least it could be an interesting tech demo to a certain group of people like me.

Aside: Wordbots as a Symbolic AI island in an LLM world

Around this time, there was, of course, a much more significant development in the NLP world – the November 2022 release of ChatGPT, which changed the public conversation about NLP seemingly overnight. As I grappled with all my feelings about the rise of large language models, one thing I struggled to figure out was, “what is the place of Wordbots in the new NLP world?” After all, as cool as the Wordbots concept seemed to me, it was built on old – let’s say ancient – technology.

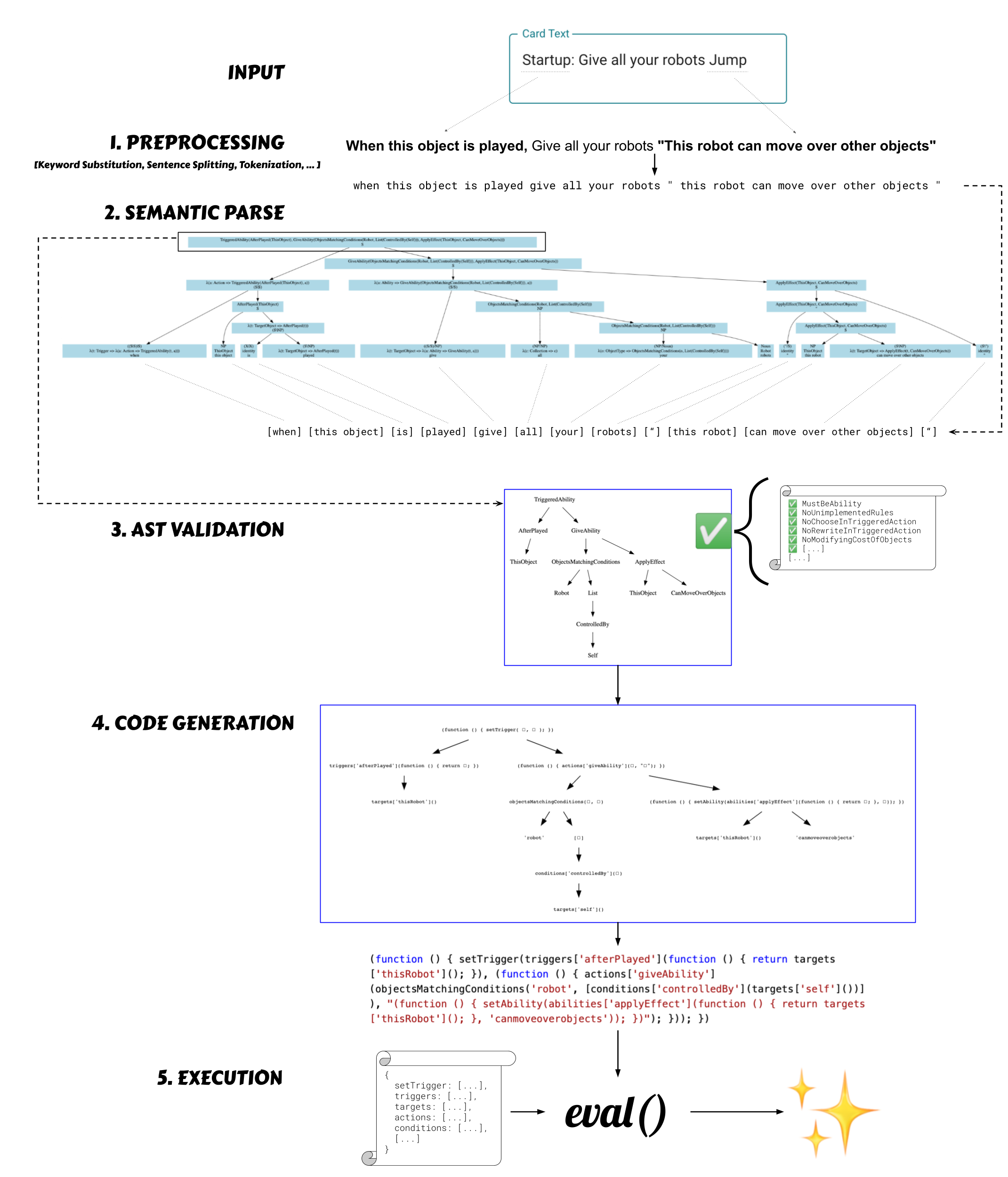

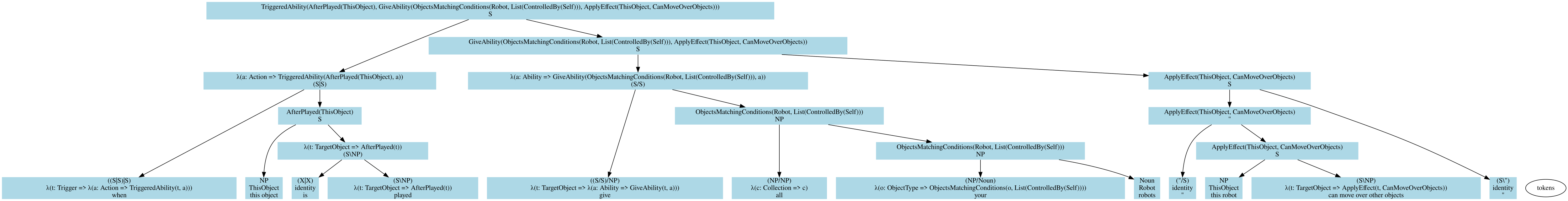

I ultimately settled on the idea of Wordbots as a demonstration of the continued relevance of older NLP approaches. As powerful as statistical NLP is today, there’s still value in symbolic AI methods. Could an LLM be used to produce code from card text the way Wordbots does? I’m sure such a thing could be implemented. Still, Wordbots’s symbolic AI underpinnings offer some valuable advantages, chiefly consistency and interpretability. Each term in Wordbots’s lexicon can be used repeatedly in consistent, predictable ways, just like natural language works, and not quite how LLMs tend to work with language. And the Wordbots parser is hardly a black box: every card in the game is happy to show off its full parse tree:

This new way of thinking about Wordbots’ purpose helped inspire me during the final push towards beta release and also led me to write the slightly cheeky “No LLMs were used in the making of Wordbots” disclaimer on the About page.

I finally began to work in earnest on checking off boxes on that old “Wordbots: The Final Stretch” doc I’d written back in 2019. Much had happened since then, but the overall roadmap was still solid, and I was able to pick up where I left off. Jacob and I started a weekly tradition of Wordbots playtests with each other, and over the next few months, we found and fixed dozens of issues with our multiplayer implementation. Other playtests helped us identify missing quality-of-life features that we proceeded to add, like support for draws, more robust game disconnection handling, support for card rarities in sets, etc. We load-tested the server to make sure it was up to the task of handling more players. We tried the game in every possible browser (including on tablets). By April 2023, we felt Wordbots had finally reached the point at which it could handle an influx of new players – it could survive in the wild.

And finally, the release! (April 2023 and beyond)

On April 29, 2023, we released Wordbots v0.20.0-beta. We were ready to show Wordbots to the world.

To me, this really meant one thing: posting it on Hacker News. I took a deep breath and made a Show HN post, writing a little about my motivation and process behind Wordbots and providing a link. And then … crickets. The post got a few likes and quickly dropped off the front page.

I was crushed. Seven years of work, and all that anguish, and all I had to show for it was a multiplayer game with no players, that nobody would ever see. And of course, I was mad at myself for having invested so much of my self-worth into a Hacker News post, and for relying so much on external validation rather than just appreciating Wordbots on its own merits. After all, wasn’t the journey the whole point?

I tried posting about Wordbots on some subreddits and my social media, but nobody seemed interested. I resigned myself to the idea that maybe Wordbots just isn’t that cool an idea to people other than me and some of my friends …

One night, a week or so after my initial HN post, on a whim (I might have been a little tipsy) I emailed dang, the Hacker News moderator, asking him if I could please re-submit Wordbots to Hacker News with a more descriptive title that better explained what was so interesting about Wordbots. To my surprise, he responded and encouraged me to re-post it. I did, and this time around the reaction was much more positive, with a constructive discussion and a whole slew of new players joining the Wordbots community and immediately creating their own unique cards.

Wordbots never became a huge phenomenon with a super active user base. And, to be fair, I didn’t expect it to (although it would have been nice!). Not having players constantly online is a bummer because when players do log in, they rarely have anyone to play with. We do have a Discord server that is occasionally active, and some players have used it to schedule games and discuss cards they’re working on.

In the year since Wordbots’s release, players have created 1441 unique cards and published 14 sets. A few die-hard Wordbots fans have gone on to make 100+ of their own cards. So that certainly feels like a small accomplishment!

I’ll admit that I haven’t spent as much time working on Wordbots post-release as I’d have liked. I made one big bug-fix release a few months after beta but lost steam afterward and haven’t done much since. I’m definitely due for at least another round of bug fixes. But remarkably, the game has continued to function even without any intervention on my part – the server is still up, the parser still works, players are still creating cards, and occasionally games are being played, all without critical bugs. I’m pretty proud of what I’ve made, and I’m glad it’s still bringing joy to people.

What went right

1. Sticking through to completion

The single thing that I’m most glad about in the Wordbots development process is that, well … we finished it! There were certainly various degrees of motivation throughout, and for a while there in 2020-2021, it seemed unlikely to me that I would ever be able to push this thing through to completion. Really, if there is one takeaway I want to offer from this massive, massive blog post, it’s “Stick with it!”

2. Investing in developer productivity

From the very beginning, investing in developer productivity was a major priority of mine. Every change to the parser’s lexicon and semantics was accompanied by unit tests verifying that given strings parsed to the right abstract representation, and it really wouldn’t have been possible to keep the parser stable without this, as even small lexical changes could have unexpected impacts on how different sentences parsed (you can check out our current test suite here). And early on in the development of the game client, I built a fairly comprehensive testing harness to make sure cards behaved as expected. (Using Redux for state management actually made this fairly simple – we had one massive reducer that handled all in-game user interactions, and most of our tests just consisted of simulating actions against this reducer and checking the resulting state.)

As our work on Wordbots continued, we made a series of major refactors in 2018–2020 – migrating the entire JavaScript codebase to TypeScript, migrating from Material UI v0 to v1, and completely overhauling how cards were stored in our Firebase database. While these refactors took an immense amount of work in the moment, they greatly improved our confidence in the code and the stability of the whole system, and I’m not sure we would have been able to get Wordbots to beta without them.

3. Soliciting feedback throughout

So much of what makes Wordbots work today – from the game formats that make games fair to all sorts of card behaviors all the way to the look and feel of the interface itself – owe their existence to player feedback. I’m really glad that we continued to playtest Wordbots and continually showed it to new people throughout the development process (even if some of the playtest rounds were demoralizing to Jacob and me due to lack of player interest).

I also just want to mention my immense gratitude to our mega-testers and sounding boards, who gave us the feedback and critique that led to so many features and fixes: Asali, James, Annie, Danny, Adam, Liam, Honza – thank you!

4. Me working throughout the whole stack, from the game client to the parser

This can also be thought of as a con (after all, it’s really a symptom of me not being able to build up a team like I wanted to), but on the bright side, the fact that I had to work on every single part of Wordbots was liberating in the sense that as I lost steam working on one part of the game, I always had the option to shift gears to other parts. This proved very helpful, especially during the lower-motivation periods – oftentimes, my gateway drug for working on Wordbots was fixing parser bugs or adding new vocabulary to the parser, as these were usually such self-contained projects that it was easy to pick up and work on them for short periods of time.

5. The Wordbots concept itself

Finally, I should mention the general Wordbots concept itself as a major “pro” – after all, it was a strong enough idea that the vision was able to push us through to the end despite all the challenges along the way! I can’t think of many projects I’d be able to work on through to completion for seven years, but this has definitely been one of them.

What went wrong

1. Struggling with motivation

In an ideal world, I would have maintained the same level of motivation that I had at the start of the project all the way through to completion. Of course, this isn’t what ended up happening. For a variety of reasons – lack of time, self-doubt, not being sure about what Wordbot’s place in the world was – I struggled with motivation at various times and had a particularly low period in 2020–2022 where I thought of Wordbots as an obligation rather than a fun project to work on.

Could I have done it differently? I could imagine a scenario where I hadn’t run out of steam by the end of 2019 and finished the Wordbots beta then. In that case, we probably wouldn’t have gotten key features like drafting formats and card rewrite mechanics – I hadn’t thought of those yet! But the core of the game would have been released to the world years earlier, with so much less mental anguish on my part. But it’s futile to think about those kinds of hypotheticals.

2. Making a multiplayer game in the first place

While Wordbots’s multiplayer gameplay is undoubtedly a core part of the experience, I do sometimes wish I’d found some way to implement my original “semantic parsing for game mechanics” idea without the multiplayer part. The issue is that multiplayer games require a community of players, and there’s a chicken-and-egg problem in that players aren’t going to keep logging in if there’s nobody to play with, so jumpstarting a community is difficult. While Wordbots does get some activity from time to time, the average visitor struggles to find anyone to play with. I don’t feel as satisfied about Wordbots’s release as I do about my last major game, Untrusted, which, as a self-contained single-player puzzle game, is always playable for anybody who wants to try it.

(The issues with building a multiplayer game also tied into my struggles with motivation, as I slowly realized that there would never be a stable Wordbots player base, causing me to question from time to time what the purpose of Wordbots even was.)

What could a single-player Wordbots have looked like? I’m not entirely sure. At one point I imagined the concept of a Wordbots “puzzle mode” (inspired perhaps by the puzzle mode in Faeria), where the player is required to win the game in one move from predetermined board positions, with the added conceit that certain cards in the player’s hand would have missing words or phrases, and the player could drag and drop from a pool of phrases to fill in the cards in a way that would make the puzzle winnable. I imagined it as kind of a Faeria (tactical card game puzzle) meets Untrusted (fill in the right words to make a level winnable) meets The Incredible Machine (drag and drop tools to complete a challenge) sort of thing. I never attempted to implement this gameplay mode, but it certainly would have been an interesting route to try.

3. Not thinking about the new player experience soon enough

It took us a long time to advance past the proof-of-concept stage, where Jacob and I sought to demonstrate that what we were building was possible from a technical standpoint. Throughout this time, we tended to prioritize new features over UX. And so, for most of our development process, Wordbots just didn’t feel inviting to new players. Even when we set out to run our biggest playtest round in 2018, we’d neglected to think about how bad the user experience was for new players; in the end, most aspiring playtesters didn’t even know what to do when seeing the Wordbots homepage for the first time.

Fortunately, we turned this around and prioritized working on the UX for new players starting around 2020, aided by some helpful alpha testers. But we missed out on a lot of good potential feedback due to Wordbots’s interface being so confusing for the first half of the development process.

4. Never finding a good way to split up work among a team

By the fall of 2018, Jacob and I had assembled a small group of developers who were passionate about the Wordbots concept and interested in helping us. Unfortunately, we never found a way to involve these eager developers in our development process. We’d have regular standups with the whole group, and Jacob and I would try to assign tasks to people, but for the most part, it still ended up being the two of us working on all development tasks (though the rest of the group still offered help in the form of playtesting and discussion of features).

I think part of the problem was Wordbots’ inherent complexity: working on the parser requires pretty specialized knowledge, while the game client is relatively thorny itself due to having to deal with arbitrary card execution as well as all of the already complex systems required to run a multiplayer game. Even tasks that Jacob and I envisioned as simple and self-contained ended up being more complicated than intended, and without easy wins, it was hard for our potential collaborators to have the confidence to approach the rest of the system.

And part of the problem was perhaps that Jacob and I aren’t great at process – we’re both better developers than we are project managers. Setting up a Zube kanban board linked to our GitHub and having occasional freeform standup meetings was about the best we could do, but it wasn’t really enough process to bring new people into the fold.

5. Spending too much time pursuing dead ends

Because Wordbots, at its core, started as a technical demo, it was easy to fall into what I could call a “hackathon mentality” while working on it. I kept falling into the trap of trying to build certain features just because they were technically interesting to work on, even if they were rarely important for the game itself.

Some examples of times that either I or other Wordbots developers got lost in the weeds:

- Automated cost calculation – A few of us briefly went down the rabbit hole of trying to have the parsing server predict how much a given card ought to cost by going through its AST, but we quickly realized that this was not remotely feasible.

- Random card generation for tests – At one point, I got intrigued by the possibility of generating completely random legal cards for various stress-testing scenarios (for both the parser and the game client). Eventually, I managed some hacky Scala metaprogramming to generate random valid card ASTs within the parser. But for some reason, I got fixated on the idea of generating random well-formed card text, by somehow inverting the parser to turn it into a generator. After spending quite some time perusing the NLP literature in search of prior art on this, I finally gave up.

- Server-side card rendering – We have a Discord bot that listens for exported Wordbot card JSON and renders the corresponding card in a readable way. Right now, it just prints a pretty text representation of the card, but for too long, I experimented with various ways to render the card as a PNG on the Wordbots server. The problem is that any technique for rendering React-to-image (and I tried quite a few techniques here) is inherently flaky, and I ran into constant struggles keeping the card-generation service working. Finally, I decided that just rendering cards as text would be sufficient for the Discord bot.

And these are just the rabbit holes that I crawled back out of! Some rabbit holes I managed to get to the end of – card rewrite effects are a good example, or, say, the Scala macro hell that I went through to be able to pretty-print lambda expressions for good-looking parse trees in Montague. So, while I certainly wasted a lot of time on these features, at least for these, I had something to show at the end of it.

6. Sticking to tools we knew

We were able to get off to a running start by leveraging tools we were already familiar with – Scala 2.10 and Montague on the parser side and the JavaScript+React+Redux+Material UI ecosystem on the client side – but this also proved to be a double-edged sword in some cases:

- Using JavaScript from the beginning instead of TypeScript led to a painful migration process as we realized how crucial the type-safety guarantees of TypeScript were for what we were doing.

- Material UI proved not to be an ideal UI framework for making things look “game-y”, and I had to mess with it intensively over many years to get Wordbots to look more like a game than like, say, a business application.

- And my deep reliance on the Scala 2.10 macro system for the parse-tree-visualization feature of Montague makes it impossible to run the Wordbots parser with any version of Scala newer than 2014. Among other issues, this means that the Wordbots parser can never compile down to JavaScript (alas, Scala.js requires Scala 2.11+) for running in the browser.

Final thoughts

I suppose I should write some kind of conclusion, but I don’t know what else I have to add at this point. Working on Wordbots was an enormous undertaking, and while the journey was rocky, I’m glad to have made it to the other side. I learned a lot from this process, and it’s definitely made me a better developer. (And maybe a better project manager, too?)

I don’t know what my next big project will be. I’m still somewhat recovering from the Wordbots process. I’d like to do something a little smaller in scope next, maybe something without an NLP component. But we’ll see!

Acknowledgements

Whew, that was a mouthful of a post! I want to end by once again thanking everyone who helped me make Wordbots a reality, from everyone who contributed code, art, or other additions to the game to all the people around the world who’ve tried making their own cards or playing a round of Wordbots. Thank you all!

Comments

blog comments powered by Disqus